MAY 4,2024

NRBALOCH

Summary of Introduction

One potentially fatal side effect of portal hypertension in cirrhosis patients is esophageal variceal hemorrhage. The current study measured the platelet count to prothrombin time (PLT/PT) ratio for the assessment of portal hypertension and subsequent diagnosis of esophageal varices (EVs) in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD), even though upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is still the preferred method for EV identification.

Techniques

Using a non-probability consecutive sampling technique, this observational comparison study was carried out at the outpatient department of Patel Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. The Patel Hospital Ethical Review Committee (PH/IRB/2022/028) granted ethical approval. For parametric data, an independent sample t-test was employed; for non-parametric data, the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized. The category data were compared using the chi-square test.

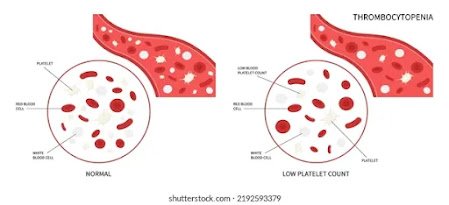

105 participants with and without EV participated in the trial. Thirty (66.7%) males and fifteen (33.3%) females did not have EV, while 38 (63.3%) males and 22 (36.7%) females did. Additionally, patients with EV had a substantially lower platelet (PLT) count (87.6 ± 59.8) than patients without EV (176.6 ± 87.7) (p < 0.001). those with EV had a PLT/PT ratio that was considerably lower (median: 5.04, IQR: 3.12-9.21) than those without EV (median: 14.57, IQR: 8.08-20.58) (p < 0.001). The PLT/PT ratio’s EV identification sensitivity and specificity were 97.80% and 83.30%, respectively.

In comparison to cases without EV, we observed a considerably decreased PLT/PT ratio in EV patients. PLT/PT demonstrated a good sensitivity in detecting cases with EVs in CLD after establishing an ideal threshold. Thus, we conclude that the PLT/PT ratio is a noninvasive predictor of the occurrence of EV in individuals with CLD.

Cirrhosis is the primary cause of morbidity and death worldwide. In 2016, it accounted for 2.2% of deaths and 1.5% of years of life with a disability adjusted for disability, making it the 11th most common cause of death and the 15th most prevalent cause of morbidity globally [1]. Chronic liver disease (CLD) claimed the lives of 1.32 million persons in 2017; nearly two-thirds of these deaths were in males and one-third in females [2]. Portal hypertension and related consequences, such as tissue scarring, mixed regenerating nodules, and liver cell degeneration, are caused by liver cirrhosis. Among Asian countries, Pakistan has the greatest incidence of CLD [3].

Clinically speaking, portal hypertension is defined as a pathological rise in portal vein pressure brought on by a number of factors, the most frequent of which being

Patient Choice

This non-probability consecutive sampling strategy was used in an observational comparison study conducted in the outpatient department of Patel Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. The Patel Hospital Ethical Review Committee (PH/IRB/2022/028) granted ethical approval. Six months were dedicated to the study. Every patient has provided written consent. 105 male and female patients with liver cirrhosis between the ages of 30 and 55 were included in the study. The study excluded patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, gastrectomy, lower portal hypertension patients on medication, patients undergoing sclerotherapy, critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis, patients with past portosystemic anastomosis, and other variables associated with ascites.

Each patient received a comprehensive evaluation that included a clinical history, laboratory testing to assess liver and renal function, total blood count, PLT, PT, and the international normalized ratio (INR). Our completely automated chemical analyzer was utilized to quantify creatinine and urea. Every laboratory test was done at Patel Hospital’s clinical pathology department. After being calculated, the PLT/PT ratios were statistically examined. After being screened for EGD, the patients were divided into two groups according to whether or not they had EV.

Every patient had upper gastroesophageal endoscopy for EVs screening in the endoscopy suite and abdominal ultrasonography in the radiology department. The treatments were carried out by skilled gastroenterologists and radiologists. The laboratory and clinical parameters were unknown to the sonologists or the endoscopists. The grading system used to categorize EV was based on size; varices in the mucosa were included in grade I; large varices that did not flatten with insufflation and occupied more than a third of the esophageal lumen were included in grade III; and varices covering more than two-thirds of the esophageal lumen were included in grade IV [16].

IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0, was used to enter and analyze the data (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). For quantitative variables, descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations; for qualitative variables, the same is true for frequencies and percentages. The data’s normality was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Patients with and without EV were compared for numerical variables; for parametric data, an independent sample t-test was employed, and for nonparametric data, a Mann-Whitney U test. To compare the categorical data of patients with and without EV, the chi-square test was employed. The PLT/PT ratio, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) cutoff points were assessed using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. An

Clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic characteristics of EV-positive and -negative individuals

105 participants with and without EV participated in the trial. There was no discernible variation in the gender distribution among them; 38 (63.3%) men and 22 (36.7%) females had EV, while 30 (66.7%) males and 15 (33.3%) females did not (p = 0.723). There was no significant difference (p = 0.899) in the mean age of patients with and without EV, which was 40.33 ± 15.98 years and 41.93 ± 12.72 years, respectively. Likewise, a negligible correlation was observed in the body mass index (BMI) between the two cohorts (p = 0.131). However, there was a notable difference in the etiology of cirrhosis across the groups (p = 0.029), with the hepatitis C virus being the predominant cause in 31 (51.7%) of the patients with EV. Individuals with EV show notably

sex

38 males (63.3%)Thirty (66.7%)0.723

22 (36.7%) female; 15 (33.3%)

Years of age 40.33 ± 15.98(kg/m2) 41.93 ± 12.72~0.899 BMI22.26 ± 5.3422.01 ± 4.25<0.131

The cause of cirrhosis

HBV~5 (8.3%)Thirteen (28.1%)0.029* HCV~21 (46.7%)~31 (51.7%)

HBV+HDV~7 (11.7%)Six (13.3%)

Immune 5 (8.3%)2 (4.4%)

The remaining 5 (8.3%)Alcoholics: 3 (6.7%) 7 (11.7%) 0 (0.0%)

1.29 ± 0.20 < 1.13 ± 0.20 INR<0.001* Albumin 3.03 ± 0.687 mg/dL3.64 ± 0.640PLT/PT; median (IQR) 5.04 (3.12-9.21) 14.57 (8.08-20.58) <0.001* Portal vein diameter (cm) 1.12 ± 0.17 1.04 ± 0.18 0.038* Child-Pugh class A 24 (40.0%) 36 (80.0%)B~26 (43.3%) <0.001*Nine (20.0%)

0 (0.0%) C 10 (16.7%)

esophageal

*p-value at least 0.05 is significant. The information is shown as mean ± SD/median (IQR), n, and percentage.

Standard deviation (SD) and body mass index (BMI) Hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis D virus (HDV) are INR is the ratio that is internationalized. Interquartile range is known as IQR and platelet count to prothrombin time ratio as PLT/PT.

There was a significant correlation (p = 0.001) between the mean hemoglobin levels of patients with EV (10.28 ± 2.08 g/dL) and those without EV (11.66 ± 2.04 g/dL). Moreover, patients with EV had a significantly lower total leukocyte count (TLC) (4.47 ± 2.33) compared to those without (6.52 ± 2.16), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.001). Patients with EV had a substantially lower PLT (87.6 ± 59.8) than those without EV (176.6 ± 87.7) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, PT, urea, creatinine, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels between the two groups showed significant differences (p < 0.001). However, there were negligible variations in sodium levels, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

(×103/m3) total leukocyte count 4.47 ± 2.33 6.52 ± 2.16<<0.00187.6 ± 59.8~176.6 ± 87.7~<0.001 Platelet count (×103/mm3)* The mean corpuscular volume was 81.2 ± 7.95 against 81.6 ± 7.53 0.789.

Prothrombin time (sec) <0.001; 14.31 ± 2.62 <12.64 ± 2.97*

Test of renal function

(mg/dL) Urea<25.5 ± 18.16~51.22 ± 53.19~<0.001* Creatinine (milligrams/deciliter)~0.80 ± 0.64~2.26 ± 3.56~0.003* Sodium 133.6 ± 20.6 137.5 ± 4.91 0.738 (mEq/L)

Test of liver function

IU/L of alkaline phosphatase: 213.5 ± 180.7 ± 201.8 ± 193.7 0.534

(IU/L) aspartate aminotransferase 86.03 ± 65.7 59.6 ± 41.1 0.134

Alanine transaminase (IU/L) 48.9 ± 43.4~0.271 54.5 ± 33.7

(IU/L) Gamma-glutamyl transferase 72.5 ± 70.9~120.0 ± 155.7~<0.001*

INR is for international normalized ratio; SD stands for standard deviation; BMI for body mass index; HBV for hepatitis B virus; HCV for hepatitis C virus; and HDV for hepatitis D virus. Platelet count to PLT/PT:Table 1: *P-value significant at <0.05, the etiology, grading, and demographics of esophageal varices (n = 105). The information is shown as mean ± SD/median (IQR), n, and percentage.

Standard deviation (SD) and body mass index (BMI) Hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis D virus (HDV) are INR is the ratio that is internationalized. Platelet count to prothrombin time ratio (PLT/PT); prothrombin time ratio (IQR): interquartile range; interquartile range

There was a significant correlation (p = 0.001) between the mean hemoglobin levels of patients with EV (10.28 ± 2.08 g/dL) and those without EV (11.66 ± 2.04 g/dL). Moreover, patients with EV had a significantly lower total leukocyte count (TLC) (4.47 ± 2.33) compared to those without (6.52 ± 2.16), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.001). Patients with EV had a substantially lower PLT (87.6 ± 59.8) than those without EV (176.6 ± 87.7) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, PT, urea, creatinine, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels between the two groups showed significant differences (p < 0.001). However, there were negligible variations in sodium levels, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

(×103/m3) total leukocyte count 4.47 ± 2.33 6.52 ± 2.16<<0.00187.6 ± 59.8~176.6 ± 87.7~<0.001 Platelet count (×103/mm3)* The mean corpuscular volume was 81.2 ± 7.95 against 81.6 ± 7.53 0.789.

Prothrombin time (sec) <0.001; 14.31 ± 2.62 <12.64 ± 2.97* Test of renal function

(mg/dL) Urea<25.5 ± 18.16~51.22 ± 53.19~<0.001* Creatinine (milligrams/deciliter)~0.80 ± 0.64~2.26 ± 3.56~0.003* Sodium 133.6 ± 20.6 137.5 ± 4.91 0.738 (mEq/L)

Test of liver function

IU/L of alkaline phosphatase: 213.5 ± 180.7 ± 201.8 ± 193.7 0.534

(IU/L) aspartate aminotransferase 86.03 ± 65.7 59.6 ± 41.1 0.134

Alanine transaminase (IU/L) 48.9 ± 43.4~0.271 54.5 ± 33.7

(IU/L) Gamma-glutamyl transferase 72.5 ± 70.9~120.0 ± 155.7~<0.001

The hepatic and renal function tests as well as the total blood count were compared between individuals with and without esophageal varices in SDTable 2. *p-value significant at <0.05. The information is displayed as n, %/mean ± SD.

Standard deviation (SD) and hemoglobin (Hb) are two different concepts.

According to the receiver operator characteristic curve, the PLT/PT ratio is a significant predictor of EV, with an AUC of 0.823 indicating good discriminative ability and an extremely substantial correlation (p < 0.001). 2.5487 was the ideal cutoff value for the PLT/PT ratio. Table 3 and Figure 1 demonstrate the sensitivity and specificity of the PLT/PT ratio for EV identification, which were 97.80% and 83.30%, respectively.

To diagnose portal hypertension, a number of diagnostic procedures are available. Directly measuring portal pressure is an intrusive procedure. Therefore, a minimally invasive approach like an upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy is preferred [17]. The gold standard for diagnosing gastroesophageal varices is still upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE), but in patients with CLD, the ratio of PLT/PT may be important for evaluating portal hypertension and EV.

It’s interesting to note that a different study evaluated the noninvasive EV markers’ diagnosis accuracy in cirrhosis patients. That investigation found that the PC/SD ratio’s optimal cutoff value was ≤818 and that its sensitivity and specificity were, respectively, 92.05% and 60% (AUC: 0.835) [24]. A different Chinese study with a 73% positive response rate likewise used PSDR <909 as a cutoff number.

This research has certain restrictions. Only cirrhotic patients were included in this short, single-centered investigation. Despite the fact that numerous studies have shown that the PC/SD ratio is a more accurate way to estimate the size and grading of varices, we only employed PLT to evaluate the grading of varices. Cherry red patches, or other indicators of recent or impending bleeding, were not seen in this investigation. It is advised that future multicenter research employ the spleen size ratio, early bleeding symptoms, and a particular cirrhosis cause. To validate the findings, more prospective studies with a larger sample size are required.

PLT/PT was observed to be considerably lower in patients with EVs who had underlying CLD in this study. We discovered that the PLT/PT value had a high sensitivity and specificity in recognizing EVs after establishing an ideal cutoff. Therefore, the results suggest that the PLT/PT ratio is a noninvasive marker of EV occurrence in CLD patients. To create a prediction score and look at other markers and predictors of esophagogastric variceal bleeding, more research is required.

Cheemerla S, Balakrishnan M: Chronic liver disease: worldwide epidemiology. 10.1002/cld.1061 in Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken), 2021, 17:365–70.

Sepanlou SG, Safiri S, Bisignano C, et al.: A comprehensive analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 of the national, regional, and worldwide burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017. 2020; 5:245–26; 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30349-8; Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Genetic predisposition to chronic liver disease in Pakistani individuals Raja AM, Ciociola E, Ahmad IN, et al. 2020, 21:3558 in Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms21103558

Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, et al.: Esophagogastric varices bleeding risk factors. Journal of Japan Medical School, 2013; 80:252–259. 10.1272/jnms.80.252

Kibrit J, Khan R, Jung BH, Koppe S: Portal hypertension: Clinical assessment and therapy. (2018) Semin Intervent Radiol. 35:153–159.